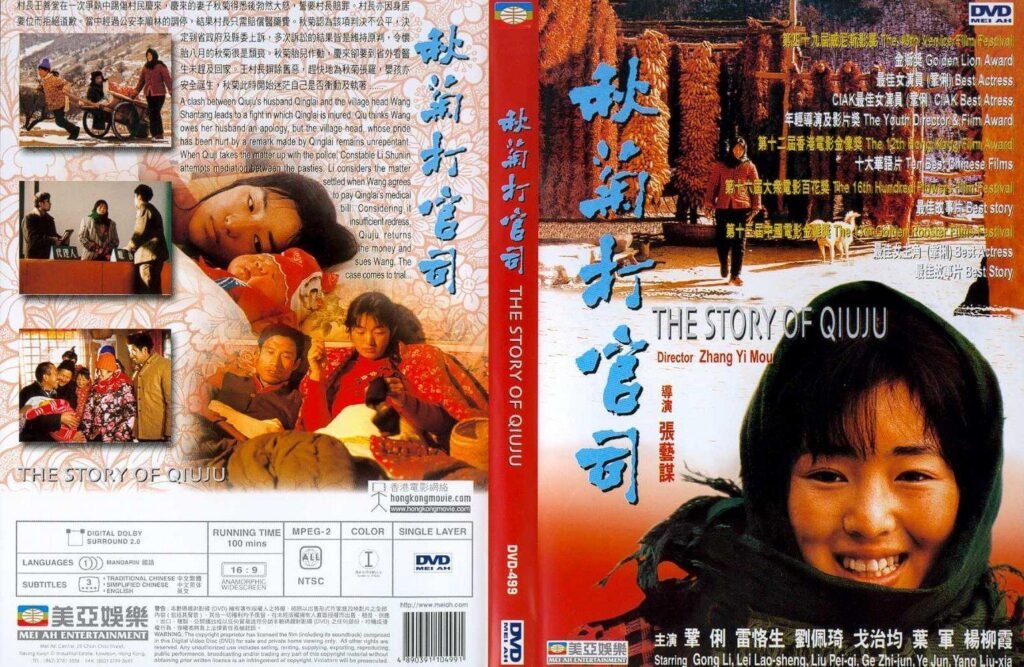

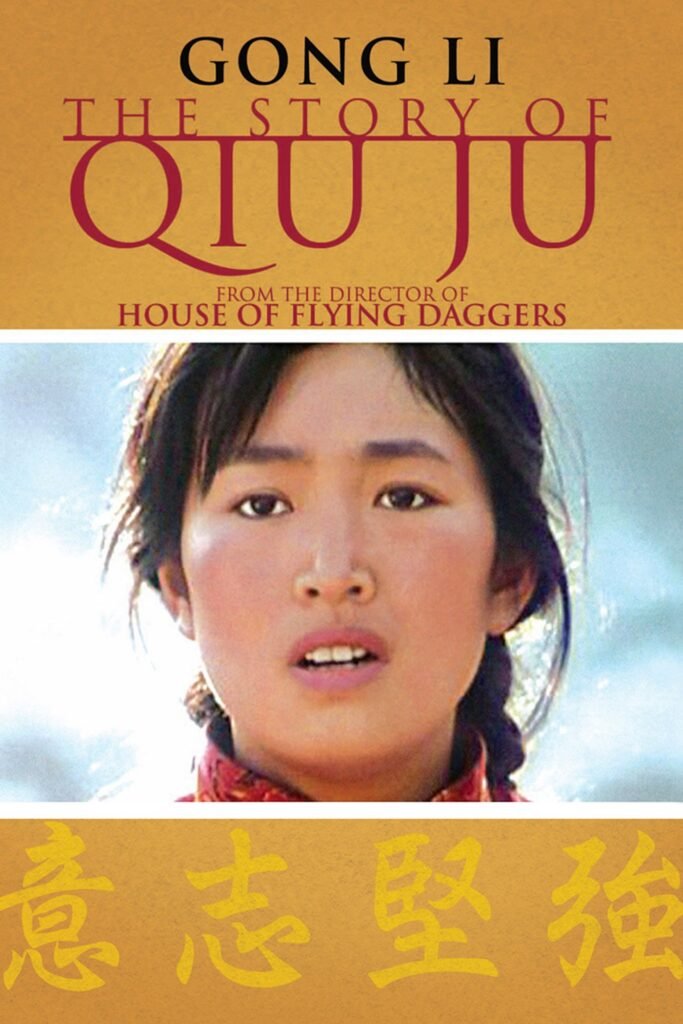

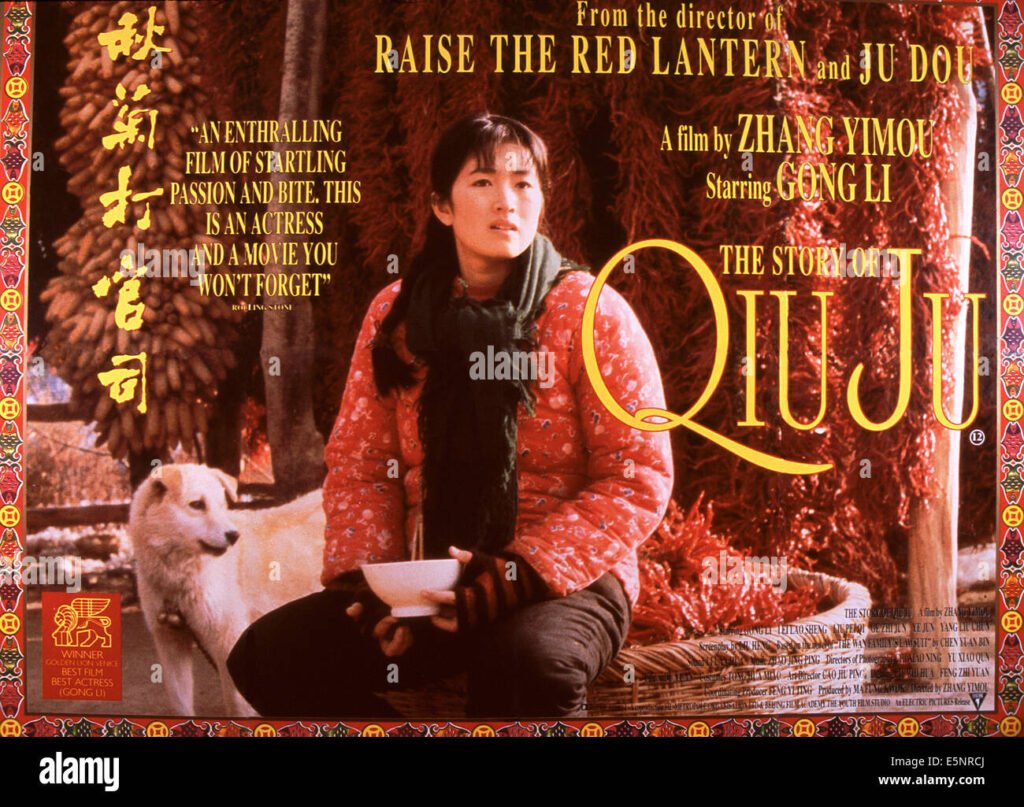

“The Story of Qiu Ju,” a film that is frequently shown in “Jurisprudence” classes in Chinese law schools and has inspired numerous theses and evaluations in academic circles, is set in a mountainous village in Shanxi, one of China’s northern provinces. The reason this film is closely examined by the legal community is due to its detailed portrayal of how a peasant woman exhausts every step within the Chinese legal system, while also showing the simplicity of the challenges and ease of reaching legally satisfactory decisions.

Particularly with the “Open Door Policy” initiated by Deng Xiaoping, China underwent significant legal reforms after 1978. Unlike the direct implementation of laws seen in the Turkish Revolution, China’s legal system has evolved by blending traditional methods with modern ones. For example, while mediation is a relatively new concept in Turkish law, it has long been one of the most traditional methods of dispute resolution in China and is still in use today.

The main storyline of the film revolves around an incident in an agricultural village, where the village chief, elected by the villagers to oversee farming activities, pushes a villager, causing a minor injury. Qiu Ju, unable to accept the fact that her husband, Qing Lai, was roughed up by the chief, approaches the village police chief to demand an apology. The police chief acts as a mediator, resolving the matter with 200 yuan for Qing Lai’s medical expenses.

The village chief, claiming he was “just following orders,” implies that his position as chief, granted by the state, puts him above the villagers. However, the police officer refutes this by stating that orders do not give him the right to harm others, underscoring that no one, not even a state official, has the authority to inflict harm. Yet, the chief’s refusal to apologize and Qiu Ju’s insistence on an apology, rather than money, turn a simple disagreement into a full-blown legal case.

The chief’s refusal to apologize stems from his fear of losing face in front of those he governs, as he is the most powerful figure in the village, responsible for overseeing its needs and issues. Although the villagers elected him, he remains accountable to both the people and the state. From the chief’s perspective, apologizing would diminish his authority, which is why even the police refrain from pressuring him to apologize, as the police, being state officials, also need strong figures like the chief.

Dissatisfied with the mediation in her village, Qiu Ju escalates the issue to the district and provincial police stations, eventually filing a lawsuit on behalf of her husband at the People’s Court. Unlike modern legal systems, legal representation or direct advocacy is not required—Qiu Ju’s application on behalf of her husband is sufficient, showcasing a distinct feature of China’s legal system. Another key aspect of the Chinese legal process is its affordability and efficiency, as Qiu Ju repeatedly files legal appeals throughout the film, which, in contrast to Western legal systems, are extremely inexpensive.

As the dispute grows more complicated, both the chief and the village police become increasingly worried. While mediation is the most common resolution method in China, legal cases often imply that the police have failed in their duties. Each time Qiu Ju appeals, a decision from a higher authority arrives, causing concern among local officials. The film effectively portrays the fears of these village administrators. Furthermore, no one opposes Qiu Ju’s appeals, illustrating how easily Chinese citizens can access the legal system and how the state subtly encourages this.

The climax of the film occurs when Qiu Ju appeals to the People’s Court, suing Police Chief Yan, who had previously resolved the case. Yan advises her to seek legal counsel and assures her that suing him would not be a problem. However, when Qiu Ju sees the polite and kind Yan as the defendant, she hesitates to continue the case, viewing it as disrespectful. This moment highlights the clash between modern legal procedures and traditional mediation, showing how Qiu Ju, like many Chinese citizens, is caught between these two systems.

One of the most striking points of the film is how a woman, unaware of legal processes, persistently seeks justice for her wounded pride, even taking her case to the Supreme Court. Despite reconciling with the chief, Qiu Ju remains unsatisfied when the court intervenes and imposes penalties on the chief. Although she had several opportunities to drop the case, Qiu Ju realizes too late that the legal process no longer concerns her personal satisfaction; the law only applies its rules, indifferent to personal emotions.

After 1978, China adopted elements of Western legal systems without directly copying them, blending traditional and modern legal principles. “The Story of Qiu Ju” is a highly valuable film for anyone seeking to understand China’s legal system and its citizens’ access to justice.