Wuxi is not a city suddenly selected and added to UNESCO’s Creative Cities Network in the field of Music. It is a city whose living musical culture draws deeply from its historical roots, spreads this heritage across generations, and continues to inspire other regions of China industrially and artistically. The Meicun Erhu Production Park (梅村二胡产业园) is a strong example of this. Although this location is not the exact origin of Wuxi’s traditional instrument, the Erhu, it is Wuxi that introduced the instrument to China and to the world. As the Erhu became more widely known, demand and interest among musicians grew significantly.

At this point, with support from the local government, a dedicated production center was established, employing artisans specialized in Erhu craftsmanship. Thousands of handmade Erhu instruments find their place in the Chinese market each year. It is estimated that 50,000 Erhus are produced in this center annually—constituting roughly 25% of China’s entire Erhu market.

Each Erhu undergoes a long and labor-intensive crafting process, leaving behind a fascinating production story. The drum-like resonating body of this string instrument is traditionally covered with python skin. When asked why, artisans explain that python skin produces the richest sound compared to other materials. Today, these skins are sourced—under strict international regulations—from python farms in Vietnam and Myanmar. Historically, however, the Erhu is a musical instrument originating from Northwest China. When asked what type of hide was used in ancient times—during periods when python trading would have been impractical—there is no definitive answer. This is because the standardized production method of the Erhu is relatively modern. While today’s high-end instruments are made of highly valued ebony or red sandalwood, early Erhus were reportedly made even from bamboo. The person most responsible for this standardization is the blind Erhu master A Bing (阿炳).

The artist, whose real name was Hua Yanjun (华彦钧) and who lived from 1893 to 1950, is now regarded as one of Wuxi’s greatest cultural figures. His fame and prestige come from his legendary composition “Moon Reflected on Second Spring” (二泉映月). The title refers to a famous historical site in Wuxi known as the Second Spring (第二泉 – Dì Èr Quán). This sorrowful and deeply emotional piece has inspired Chinese and international musicians alike. The work gained global recognition after Seiji Ozawa, the Japanese conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, visited China in 1978. Upon hearing the piece performed on the Erhu, he famously said:

“While listening to such a piece, one should fall to their knees.”

Following this experience, Japanese and many international orchestras adapted the composition and performed it widely. Today, at the center of Liangxi District (梁溪)—a popular ancient town open to visitors—one can see a modern artistic monument dedicated to A Bing. However, this area is not merely a commemoration of a historical artist; it is designed as a living music city. Even in ordinary cafés, visitors will find vinyl records of classical works on the walls, short texts telling their stories, and headphones offering immersive listening experiences.

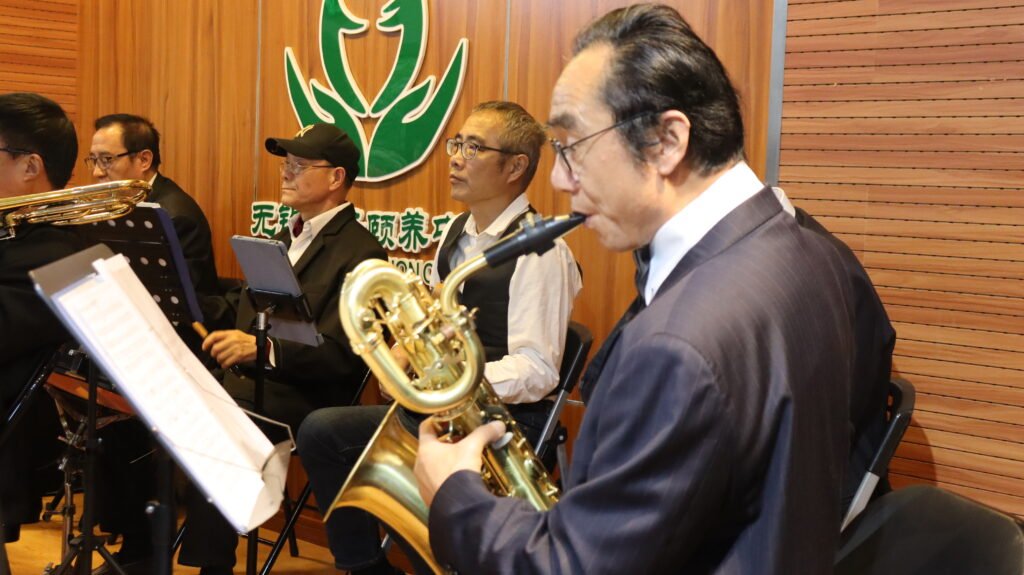

Wuxi’s living musical culture is also not limited to tourism areas. In facilities known as “Universities for the Elderly” (老年大学)—essentially advanced care centers—an extensive music program is implemented. These programs are not for the musically talented alone: people from many age groups reconnect with music here through lessons, courses, and even organized concerts. Rather than passive care centers visited occasionally out of obligation, these places function as real learning and cultural hubs. Performances and music events are part of the weekly—and sometimes daily—routine. Visitors will not see residents withdrawn from life, but rather senior “students” who are still learning, creating, and actively participating. This is not something that can be achieved through external pressure; it reflects the region’s deeply rooted musical lifestyle.

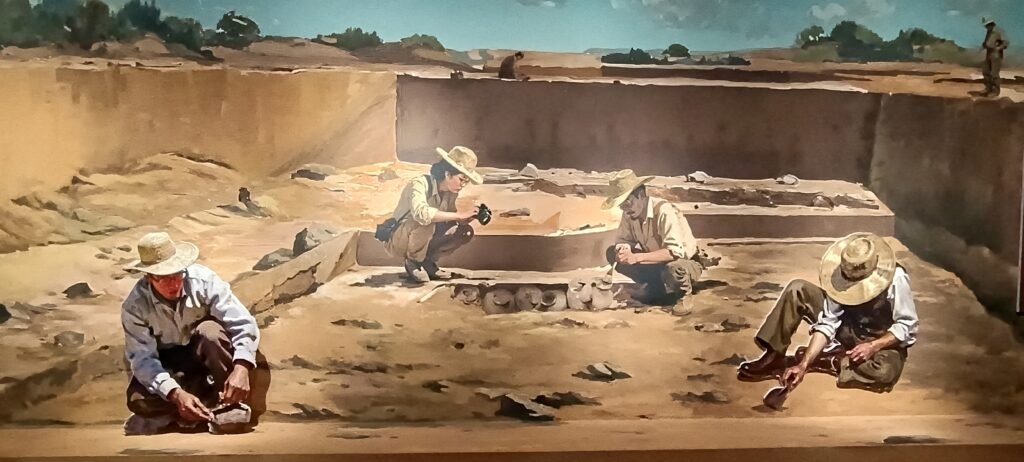

The Hongshan Yue Tombs provide further insight into the prehistoric communities that lived in Wuxi during the pre-imperial kingdom eras, particularly their musical culture and daily habits. For example, during the Zhou Dynasty, the number, variety, and size of musical instruments a person possessed reflected their social rank and status. Only the king had the right to play a certain number of bronze bells (编钟). Connected to their belief in life after death, the Yue (越) people believed that whatever life they led on earth, they would continue in the afterlife. Archaeological findings reveal that nobles of the Yue State violated the strict rule of “only the king may possess certain bells” in order to ensure a more luxurious afterlife. They were buried with instrumental sets far exceeding their status—similar to burial practices in Ancient Egypt, where people were interred with their most valuable possessions.

Additionally, excavations in the region uncovered not only ordinary bells and drums but also instruments with shapes and sounds distinct from traditional Chinese bells, indicating that this region had developed its own unique musical identity. Thus, the musical journey that began with the cultures of Wu (吳) and Yue (越) has evolved into the vibrant musical city Wuxi is today—and continues to inspire many communities.

Abroad Africa AI Beijing Belt & Road BLCU BRICS China chinese CPC CSC Culture Economy education EU Guizhou Kültür Langauge movie Multipolarity Russia scholarship science Shanghai Sino Sino Turkish Sino Turkish Sino Turkish Sino Turkish Sino Turkish Studies Sino Turkish Studies Sino Turkish Studies Sino Turkish Studies space Syria Taiwan Tariff trump Turkiye Türkiye University USA Xinjiang ZJUT Çin