China’s Yangtze River Delta is a world heritage site that hosts unique natural beauty and a wide variety of living species. The Chinese government shows utmost sensitivity to protecting this ecological richness through both national and local programs. Today, observing many species of birds, snakes, foxes, and deer without barriers is a priceless gift, yet these creatures have also been a source of inspiration that has shaped unique Chinese art throughout history. The accumulation of knowledge and culture that Chinese society has built over thousands of years of settled life has undoubtedly been shaped by the beauty that nature has offered them.

1. Red-Crowned Crane (丹顶鹤, Dāndǐng Hè)

The Red-Crowned Crane is considered a symbol of luck and dignity in Chinese culture. Today, Yancheng, which is under protection, forms an important wintering ground for this species along its migration route. Breeding in Siberia, the cranes migrate southwards to the Yangtze River region to escape the destructive cold. The wide reed beds, shallow waters, and abundant food sources offered by the region are highly attractive for these birds. This journey, which has continued for thousands of years, has also been a great source of inspiration for local communities.

In Turkish culture, these migratory birds, as symbols of travel, have often been depicted in artworks with the theme of gurbet (longing for home). In Chinese culture, however, the emphasis is on their role as eternal beings within a continuous ecosystem.

The Red-Crowned Crane embodies concepts such as “immortality, wisdom, and nobility.” According to Taoist belief, immortals often travel on the backs of cranes. Thus, cranes were seen as a bridge to immortality. Because of their association with immortals, cranes were believed to have long lifespans; they became a popular theme in birthday celebrations and gifts expressing respect for elders. In Chinese painting, cranes were often depicted together with Pine Trees (松鹤图, Sōng Hè Tú), as pine trees do not shed their leaves even in winter. In Traditional Chinese Opera (京剧, Jīngjù), although there is no direct crane character, the elegant movements of the opera were inspired by the walking style of cranes. Especially in portraying noble characters, the movements of cranes were directly imitated.

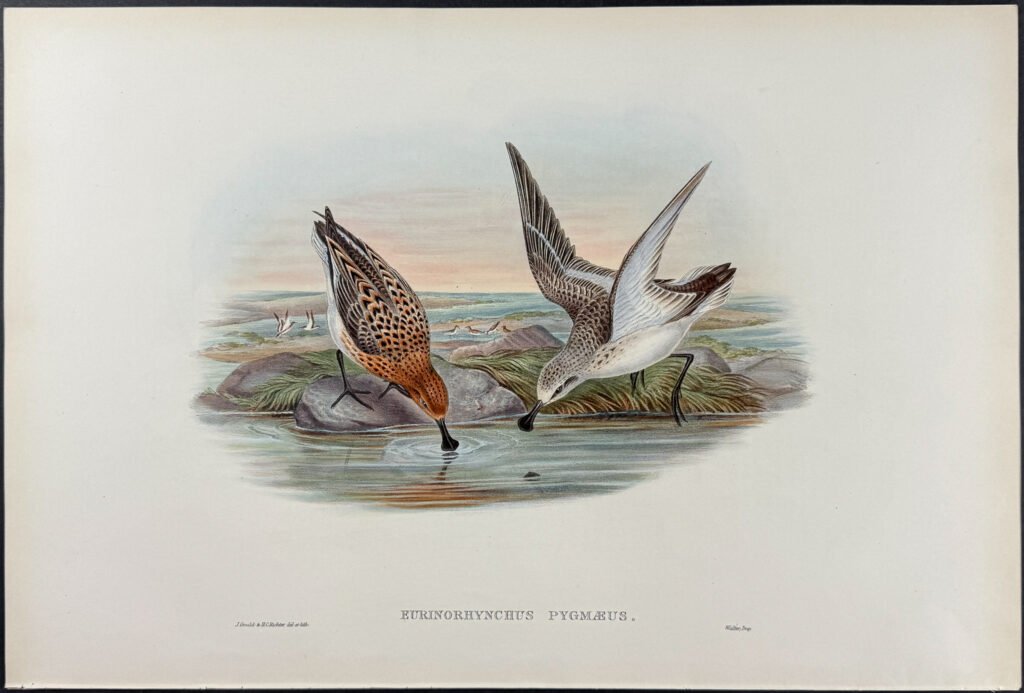

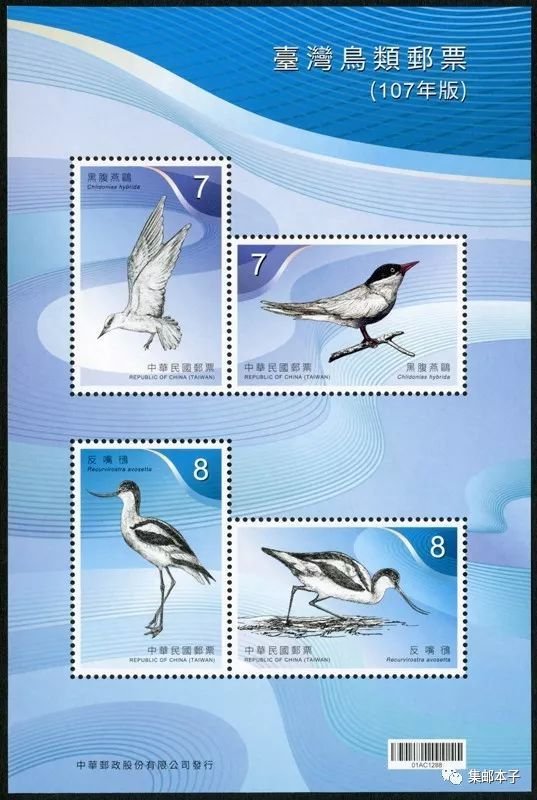

2. Spoon-billed Sandpiper (勺嘴鹬, Sháozuǐ Yù)

Now a mascot for the region’s promotion, the Spoon-billed Sandpiper takes its name from its spoon-shaped bill. It is one of the world’s rarest and most endangered bird species, with an estimated adult population of only 200–400. Like the cranes, this bird breeds in eastern Russia and follows a similar migration route to spend the winter.

Unlike cranes, the Spoon-billed Sandpiper is almost never found in traditional Chinese art. This is because it is a relatively small and timid species that lives on remote rocks, rarely interacting with human populations. Its discovery and promotion are also relatively recent.

Its absence in traditional art has now been replaced by its increasing presence in modern art, thanks to active promotion by the scientific community. Artists focus on its cute spoon-shaped bill to evoke sympathy and raise awareness for conservation. Its small size and endangered status make it a strong symbol for themes of “fragility” and “innocence.” Today, the Spoon-billed Sandpiper is the main figure on posters for wetland protection projects in China and around the world (such as BirdLife International and WWF). In 2020, it was featured in a stamp series by China Post dedicated to wetland birds.

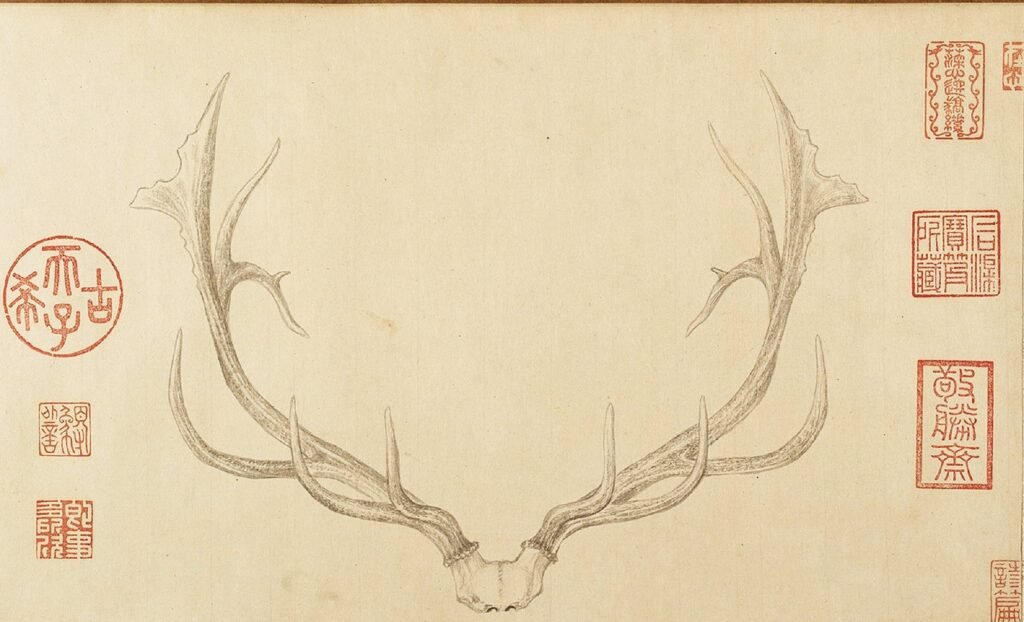

3. Deer (麋鹿, Mílù)

An endemic species unique to China, also known as Père David’s Deer, this deer was historically native to the region. At the beginning of the 20th century, due to overhunting and lack of awareness, its wild populations became completely extinct. The last remaining individuals were transferred to zoos in England and Europe. In the 1960s, China launched a program called “Return to the Motherland,” and today a massive conservation center now hosts thousands of deer.

Therefore, the Milu deer holds great significance both in traditional and modern history. In pre-Islamic Turkish culture, deer often symbolized guides to ascension to the heavens, depicted in carpets and kilims. In Chinese culture, due to imperial heritage, it stood out as a symbol of nobility.

The Milu deer is known in China as the “Four Unlikes (四不像, Sì Bù Xiàng)” because its antlers resemble a deer, its neck a camel, its hooves a cow, and its tail a donkey. This unique appearance made it a mythological figure in Chinese art. During imperial times, they were kept in royal hunting parks, and commoners were forbidden to hunt them, reinforcing their noble meaning. The word “deer” (鹿, lù) shares the same pronunciation with “salary/prosperity” (禄, lù) in Chinese, so deer motifs symbolized luck, promotion, and wealth. Especially in the Ming and Qing dynasties, deer were frequently depicted on vases and ornaments. In imperial clothing, deer motifs represented high rank and nobility. In traditional paintings, they symbolized peace, abundance, and longevity.

4. Stork (东方白鹳, Dōngfāng Báiguàn)

Also called the “Oriental Stork,” this species, like cranes and sandpipers, breeds in the Far East and migrates southwards to spend the winter. These birds are especially known for building their nests on tall man-made structures in recent years. Constantly caring for their young in full view of human populations has caused them to be associated with the idea of the “stork bringing babies,” similar to Western culture.

Storks (鹳, guàn) hold significant importance in Chinese culture. Like cranes, they were believed to live for a thousand years. They were often depicted together with pine trees and especially peach trees (寿桃, shòutáo), symbols of longevity.

Ming and Qing dynasty vases and plates were frequently decorated with stork motifs. Because of their association with bringing babies, storks were also embroidered on children’s clothing, bedding, and wall panels as symbols of blessing for families and wishes of longevity for children. Their long legs, majestic stance, and habit of nesting in high places inspired Chinese poetry, where storks symbolized lofty goals, nobility, and freedom. Traditionally associated with long life, today storks are still widely used in the logos of healthcare institutions, pharmacies, and family-owned businesses in China.

5. Fox (狐狸, Húli)

Unlike the other animals, foxes are not typical wetland creatures but are more commonly found in dry scrublands and forests. However, in the Yancheng and Yangtze Delta regions, they play an important role in controlling rodent populations, directly contributing to the sustainability of the ecosystem. Beyond their ecological role, foxes’ carnivorous nature has given them a dual role in Chinese culture—representing cunning and trickery on one hand, and wisdom and spirituality on the other.

Perhaps the most important theme surrounding foxes in Chinese culture is the “Fox Spirit (狐狸精, Huli Jing).” According to legend, a fox that accumulates Taoist energy for a thousand years gains magical powers and can transform into a beautiful, seductive woman. This often serves as a metaphor for sexuality and human weakness. Pu Songling’s classic work Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio (聊斋志异, Liáozhāi Zhìyì) explores these fox spirits, sometimes dangerous, sometimes compassionate. The 2019 animated series Love, Death & Robots also featured this story in the episode “Good Hunting.”

Outside this role, foxes were also seen as messengers of goddesses, representing wisdom. In Traditional Chinese Opera, the fox spirit falls into the “Hua Dan” (young woman role) category. Characters often wore white or silvery costumes, imitating the agile, seductive, sly, and sometimes timid movements of foxes. Thus, while the fox (狐狸, Húli) is the silent guardian of the Yancheng ecosystem, it has also become a strong psychic figure shaping Chinese art and culture.

(Sanat)

Abroad Africa AI Beijing Belt & Road BLCU BRICS China chinese CPC CSC Culture Economy education EU Guizhou Kültür Langauge movie Multipolarity Russia scholarship science Shanghai Sino Sino Turkish Sino Turkish Sino Turkish Sino Turkish Sino Turkish Studies Sino Turkish Studies Sino Turkish Studies Sino Turkish Studies space Syria Taiwan Tariff trump Turkiye Türkiye University USA Xinjiang ZJUT Çin