The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), presented to the world by Chinese President Xi Jinping during his 2013 visit to Kazakhstan, first came under attack through the “Debt Trap Diplomacy” propaganda by Indian “thought leader” Brahma Challaney in 2017.1 Since then, Western countries have clung to this term, targeting the BRI, which leads the reshaping of the international order. According to this false campaign, China is supposedly indebting countries through the BRI in an unrepayable manner, making them dependent and increasing its political influence over them. Sri Lanka and Malaysia were chosen as the main targets of this criticism.

Recent developments in Sri Lanka have provided Western countries, especially the United States (US), with an “opportunity” to spread the narrative of “China indebted, people revolted” once again. This article will address Sri Lanka’s external debt problem and the “debt trap” lie related to the BRI.

SRI LANKA’S EXTERNAL DEBT ISSUE

Sri Lanka, a small but strategically located country on the Indian Ocean and part of the BRI’s “21st Century Maritime Silk Road,” has seen its economy grow rapidly since the end of its civil war in 2009, but its external debt stock and economic risks have also increased. The core of Sri Lanka’s external debt issue lies in the challenge of how to achieve post-civil war economic recovery and catch up with development.

THE FIRST DEBT FROM THE WORLD BANK

In 1954, Sri Lanka took its first external debt of 130 million Sri Lankan Rupees from the World Bank to meet its internal financing needs.2 Sri Lanka then began borrowing from various Western financial institutions and governments. By 1983, Sri Lanka’s total external debt reached 46 billion rupees, entering a serious external debt crisis and taking on more new external debts to pay off existing ones. Contrary to claims, the borrowing was mainly from Western countries and financial institutions, not China!

When Mahinda Rajapaksa came to power in 2005, Sri Lanka’s Debt/GDP ratio was 91%. With the end of the 40-year civil war in 2009 under Rajapaksa, the country achieved sustainable growth, the value of its currency stabilized, domestic and foreign investments increased, interest rates fell, fiscal deficits were controlled, and inflation was managed. Sri Lanka’s Debt/GDP ratio dropped to 71% by January 2015 (a 20-point decrease over 10 years).3

However, with the government of Maithripala Sirisena taking office in 2015, the country’s debt once again reached unacceptable levels. The former governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka announced that the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio rose to 81% in 2017.

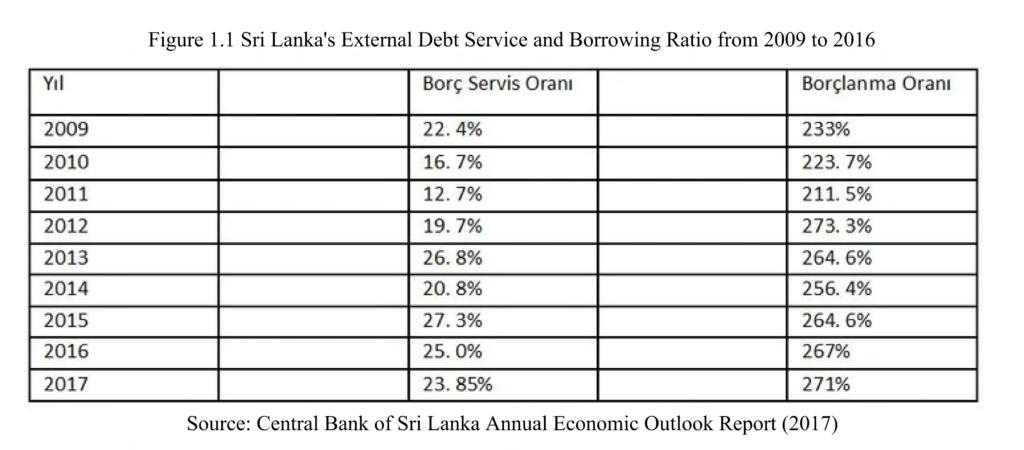

Economic indicators suggest that although Sri Lanka’s external debt burden continued to increase from 2011 onwards, debt repayment risks were expected to be manageable. The issue fundamentally arises from imbalances in domestic production, foreign trade, fiscal expenditures, and debt management. Here, China extended a helping hand with “mutual development” principles within the framework of the BRI, signing a series of commercial agreements with the Sri Lankan government.

THE BRI’S HELPING HAND

According to the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, from 2009 to 2017, Sri Lanka’s total external debt more than doubled in less than a decade, from 20.913 billion dollars to 51.824 billion dollars.

Thanks to the BRI, Chinese investments began to alleviate the debt crisis created by unproductive financing from Western countries and institutions. By the end of 2015, a significant portion (50.5%) of Chinese loans was used for economic services, with investments in ports, highways, and irrigation systems starting under the BRI, highlighting the positive impact on infrastructure projects and employment growth compared to Western investments.

MOST OF THE EXTERNAL DEBT TO WESTERN MARKETS!

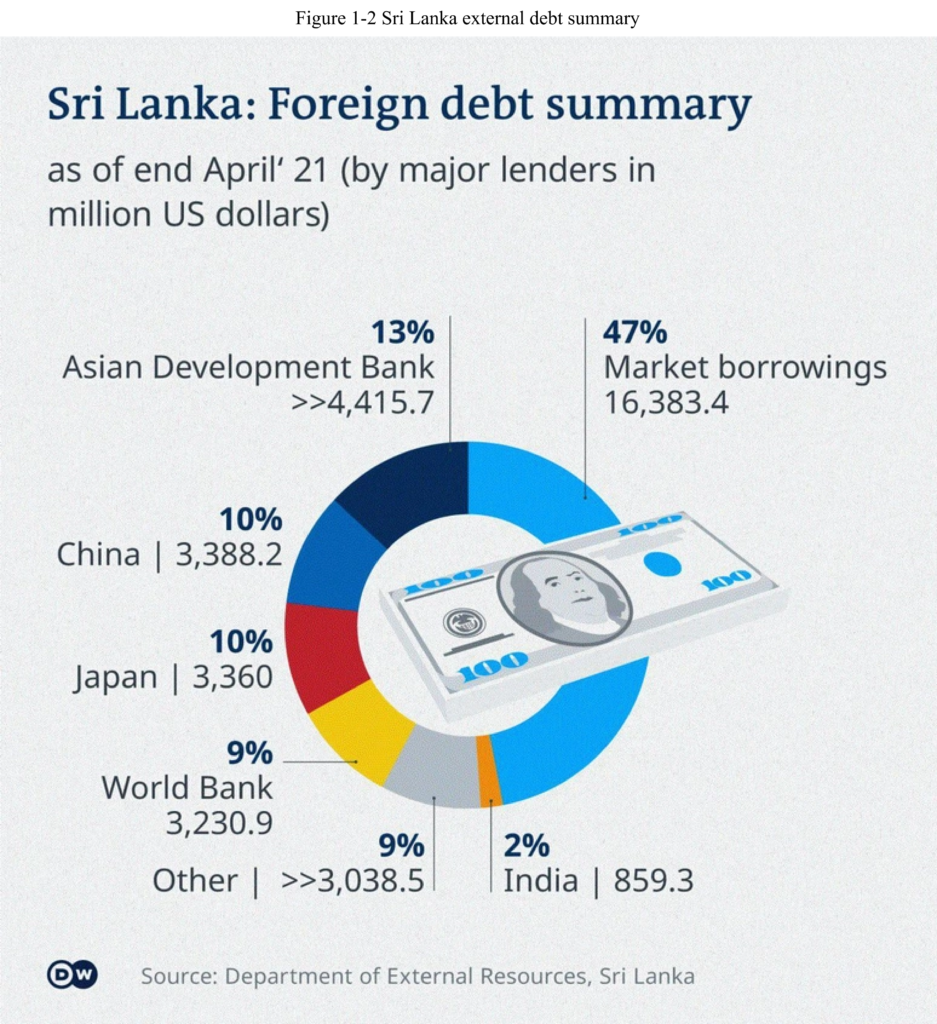

Sri Lanka’s external debt is primarily divided into three categories: sovereign external debt (with China and Japan as the main creditor countries); international and regional multilateral financial institutions, including the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF); and the international finance market (mostly to Western countries or institutions).

Sri Lanka’s international debt issue lies not with China but in the sovereign markets of the West, with three-quarters of its debt owed to financial institutions (See Figure 1-2).

Sri Lanka’s external debt problem began in the 1960s and has escalated ever since. The country created a “vicious cycle” by taking on new external debts to pay off old ones. Long-lasting internal conflict, political unrest, social conflicts, and missed opportunities for industrialization and development due to the inability to leverage economic ties with East and Southeast Asia have led to a dependency on external resources. Sri Lanka primarily exports primary products due to its limited production structure, with about 85 % of its external debt being long-term, contributing to the accumulated debt burden.

With the pandemic, foreign capital, predominantly of Western origin, began leaving Sri Lanka, causing the Sri Lankan currency to plummet against the US dollar.

THE DEBT TRAP LIE

In terms of total external debt, nearly 60% of Sri Lanka’s external debt is owed to Western capital markets. Although the share of loans from China rose from 2% in 2008 to 9% in 2017, its overall share remains low. Data refutes claims of China creating a “debt trap” in Sri Lanka, as the country’s largest creditors are Western financial institutions, the US, European countries, and Japan. In 2017, Sri Lanka’s external debt balance was 51.824 billion US dollars, with loans from China constituting about 5.5 billion US dollars, making up 10.6% of the total external debt. Moreover, 61.5% of loans from China are concessional, with long repayment periods, not constituting the main burden of Sri Lanka’s external debt.4

Additionally, according to a 2019 report by a Colombo-based survey company5, a majority of Sri Lankans (60%) believe that China supports Sri Lanka’s national interests. It’s clear that both Sri Lankan government officials and the public do not hold a negative view on the BRI and Chinese investments, rejecting the “debt trap diplomacy” narrative.

BRI CREATES, USA TRIES TO DESTROY

From the end of Sri Lanka’s civil war in 2009 until 2010, countries like the US, European nations, Japan, and India, along with international organizations like the IMF and the World Bank, imposed economic sanctions on Sri Lanka. The country faced division threats during the civil war, which lasted from the late 1980s to 2010, resulting in an estimated 40,000 civilian deaths. The Western embargo applied inhumanely during this period explains the external cause of the economic crisis in the country.

In conclusion, when looking at the US and CIA’s bloody history of indebting countries, overthrowing governments, and assassinations, it’s evident that the issues in Sri Lanka are not related to China but stem from US imperialism.

- Chellaney, Brahma. China’s Debt-Trap Diplomacy. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/china-one-belt-one-road-loans-debt-by-brahma-chellaney-2017-01 ↩︎

- Presbıtero A F. Total public debt and growth in developing countries. The European Journal of Development Research, 2012, 24(4): 606–626 ↩︎

- Tang Pengqi. The Current Situation, İmpact And Countermeasures Of The Debt Crisis Since Sri Lanka Kasrissena Took Office. South Asia Research Quarterly, 2018, April. ↩︎

- http://world.people.com.cn/n1/2018/0705/c1002-30129686.html ↩︎

- Values and Attitudes Survey on 70 Year of Independence in Sri Lanka: 1948–2018. Colombo, Sri Lanka: Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA). 2019. ↩︎