After the collapse of the Qing dynasty on February 12, 1912, Sun Yat-sen, as he had promised, nominated Yuan Shikai as the new president of the Republic of China instead of himself. On March 10, 1912, Yuan Shikai assumed the presidency of the Republic of China, and in April 1912, he declared Beijing the new capital of the Republic. The main reason for this decision was that his army and supporters were based in Beijing. All administrative institutions (the Provisional Senate, ministries) were transferred from Nanjing to Beijing. During this process, no organic bond could be established between the republican intellectuals and Yuan Shikai, and most republican practices remained only on paper.

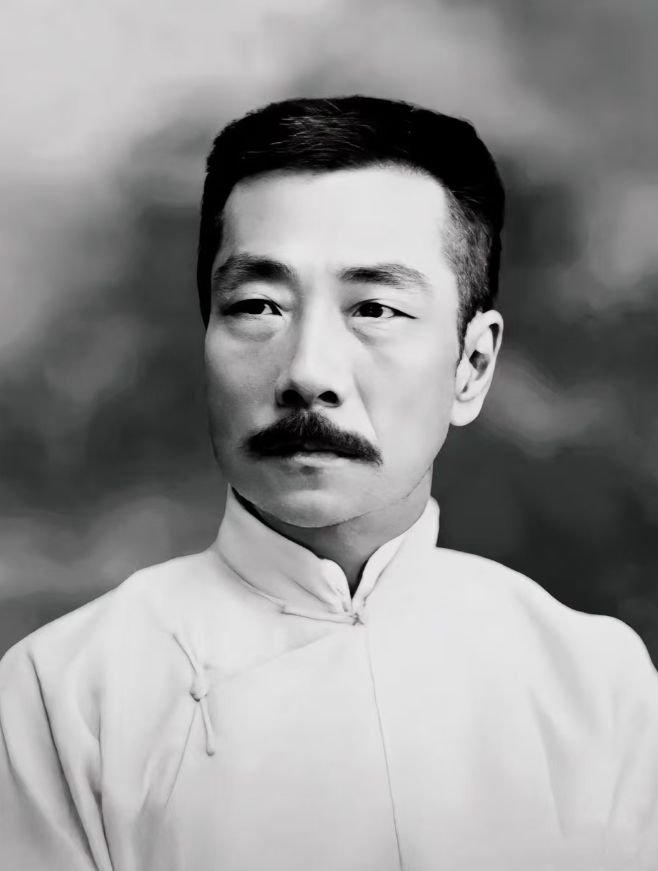

In 1912, a large number of political parties and associations emerged in China. Leaders of the Tongmenghui, such as Song Jiaoren (宋教仁, right), in opposition to Yuan Shikai’s military and political dominance and in an effort to turn the Tongmenghui into a broader coalition, began uniting with other existing parties and associations to form a more inclusive party.

The first party to bear the name Guomindang was officially established on August 11, 1912, through the merger of the Tongmenghui, the United Republican Party (Tongyi Gonghedang), the National Public Party (Guomin Gongdang), the National Progressive Association (Guomin Gongjinhui), and the Republican Practical Association (Gonghe Shijinhui). Song Jiaoren assumed the de facto leadership of the party.

Despite their different names, these parties and associations essentially pursued similar goals, most of them consisting of progressive individuals who had broken away from monarchist circles. Their common objective was to transform the political system away from monarchy toward a more rational path of change. Rather than pointing to a clearly defined vision of the future, the names of these parties and associations evoked the popular ideas of the time. Democracy, Republic, Nationalism—these terms represented the necessary steps China had to take on its journey into the future.

China’s first general elections were held between December 1912 and January 1913 under a “two-tier electoral system,” with dozens of parties participating. Yuan Shikai did not have a party of his own, but he had strong ties with parties supporting constitutional monarchy, such as the Progressive Party (进步党). In the elections, the Guomindang won 269 seats, gaining a majority in the House of Representatives. In this election, which had about 43 million registered voters (10% of the population), the Guomindang’s victory unsettled Yuan Shikai. In March 1913, Song Jiaoren, the party’s de facto leader, was assassinated at a train station.

Under heavy criticism from republicans, Yuan Shikai sought to preserve his authority across China by appointing military commanders from his army to govern the provinces. This practice laid the groundwork for what would later become the “warlord era.”

In reaction to all this, on July 12, 1913, the provinces of Jiangxi, Anhui, and Guangdong declared independence and launched uprisings under the leadership of Sun Yat-sen. The movement, called the “Second Revolution” (the first being the Xinhai Revolution), was quickly suppressed by the Beiyang Army. With the fall of Nanjing on September 1, resistance came to an end; by September 12, all fronts had fallen under Yuan’s control. This defeat led to the banning of the Guomindang and Sun Yat-sen’s exile to Japan, temporarily silencing the republican opposition.

Zhou Shuren in the Meantime

In early 1912, Cai Yuanpei (蔡元培, left), who would later become a very prominent figure, was appointed the first Minister of Education of the Nanjing Provisional Government. With the proclamation of the Republic, efforts to modernize the education system intensified. During this period, Zhou Shuren served as principal and physiology teacher at Shaoxing Middle School. Dissatisfied with the limited resources and local practices, Zhou was encouraged by his friend Xu Shoushang, who held senior positions in various institutions of the newly founded Republic and was closely connected with prominent figures in the Ministry of Education, including Cai Yuanpei himself. When Xu Shoushang mentioned Zhou to Cai Yuanpei, Cai said he had heard of him and believed it would be beneficial for Zhou to work at the ministry, sending him a formal invitation by letter.

As noted earlier, when Yuan Shikai declared Beijing the capital in April 1912, all administrative institutions, including the Ministry of Education, were moved from Nanjing to Beijing by May. Zhou remained in Nanjing for a time, then moved to Beijing with the other officials. There, he settled in the Shaoxing Hostel (会馆, right), an association-hostel established by people from the same hometown living in another city.

After the “Second Revolution,” when political tensions between Yuan Shikai and the republicans peaked, many republican institutions continued to function, but administrative practices began to revert to old habits. Imperial rituals were reintroduced at court, and in December 1915 Yuan Shikai, with the backing of his council (参政院) filled with his supporters, declared himself emperor. Faced with strong opposition outside the palace and suffering from health problems, Yuan’s imperial claim lasted only 83 days. In March 1916, the empire was abolished, and by June 1916 Yuan Shikai had died of kidney disease.

Throughout this period, Zhou Shuren worked at the ministry during the day and spent his nights copying ancient Chinese texts in his study. He later described this experience, and the writing of his first story A Madman’s Diary—the first time he used the pen name Lu Xun—in the preface to his collection Call to Arms:

The Shaoxing Hostel had three rooms. It was said that long ago a woman had hanged herself from a locust tree in the courtyard; the tree had since grown beyond reach, but still no one would live in that room. For years I stayed there, copying ancient stone inscriptions. I had few visitors, and among the stone inscriptions I found no troubles or “cases”; life passed quietly, which was all I wished for. On summer nights, when mosquitoes multiplied, I would sit beneath the locust tree with a fan in hand, gazing through the thick leaves at fragments of the sky. Sometimes the caterpillars from the tree would fall on my head and neck, chilling me.

At that time, an old friend, Jin Xinyi (Qian Xuantong), would occasionally come to talk. He would set his big leather bag on the desk, take off his long coat, and sit opposite me. Afraid of dogs, his heart seemed still to be pounding.

“What use is there in copying so many inscriptions?” he asked one night, as he flipped through my copies with a researcher’s air.

“None at all.”

“Then why copy them?”

“For no reason.”

“I think you could write something…”

I knew what he meant: they were then publishing New Youth (新青年). At the time, no one supported them, but neither did anyone oppose them. I thought perhaps they felt lonely. I replied:

“Suppose there were an iron house, with no windows, unbreakable, and inside many people sleeping soundly, doomed soon to suffocate. But because they were falling asleep peacefully, they would feel no pain in dying. Now, if you cry out to wake a few of them, these unfortunate few, once awake, would only suffer the agony of hopeless death. Do you really think you are doing them a kindness?”

“Yet since a few are awake, you cannot say there is no hope of breaking the iron house.”

Indeed, my own conviction was different; but when it came to “hope,” I could not entirely deny it. For hope belongs to the future; my “it will never be” could not destroy his “maybe it will.” So in the end I promised to write. And that was how I wrote my first story: A Madman’s Diary. From then on, I could not stop; at my friends’ request I continued writing short stories, and gradually they accumulated.

Following A Madman’s Diary, Lu Xun began publishing regularly in New Youth (新青年, right). His writings often criticized the way people were sacrificed in the name of “tradition” for the benefit of a privileged few. These critiques and reckonings—seen as the growing pains of breaking away from the feudal order—marched alongside other revolutionary forces as part of the New Culture Movement.

In the past, the words “loyalty” (节) and “valor” (烈) were also considered virtues for men. Thus, titles such as “a loyal man” (节士) and “martyr” (烈士) came into being. However, in modern times, “commending loyalty and chastity” (表彰节烈) has become reserved exclusively for women; men are now excluded from this definition.

According to today’s moralists, these concepts are defined as follows:

Loyalty (节): A woman must never remarry, run away, or engage in a relationship with another man after her husband’s death. The earlier her husband dies and the poorer her family is, the more her loyalty is praised.Valor (烈): This manifests in two ways: Whether married or not, as soon as her husband dies, the woman immediately kills herself. And In the event of an attempted rape, she either tries to kill herself or resists until she is killed. In such cases, the more painfully and under the harsher circumstances she dies, the more “valorous” she is considered.

(My View on Chastity, July 1918)

When Lu Xun wrote My Views on Chastity (我之节烈观), Chinese women were living under the crushing weight of centuries of patriarchal feudal traditions. A woman whose husband died—no matter how young she was—was expected never to remarry. She was to spend the rest of her life in suffering, dedicating herself to her children and serving her husband’s family. Sometimes she was even expected to commit suicide—or at least make an attempt. Historical records are filled with stories of countless young widows who hanged themselves or drank poison after their husbands’ deaths. Such women, who “preserved their chastity,” were praised by society, and could even be honored by the state with “chastity arches” or memorials. By contrast, a widow who wished to remarry was scorned by her family and society, stigmatized as “unchaste” and “immoral.”

If a woman sought divorce or was abandoned by her husband, it brought shame not only upon herself but upon her entire family. Society upheld the belief that “a good woman does not marry twice” (好女不嫁二夫). A divorced woman had no social status, her family often refused to take her back, remarriage was nearly impossible, and she was forced to survive by undertaking the harshest forms of labor.

In his writings, Lu Xun harshly criticized such practices, which he described as “cannibalistic.”

“Everything requires careful consideration if one is to understand it. In ancient times, as I recall, people often ate human flesh, though I am not entirely sure. I tried to look this up, but my history book had no chronology; scribbled all over every page were the words ‘Virtue and Morality.’ Since I could not sleep anyway, I read carefully into the night—until I began to see words between the lines; the entire book was filled, between the lines, with the words: ‘Eat people.’”

(A Madman’s Diary, Chapter III, April 1918)

“Perhaps there are still children who have not eaten human flesh? Save the children…”

(A Madman’s Diary, Chapter XIII, final chapter, April 1918)

To be continued in the next article…