In our previous article, we covered the period from Lu Xun’s birth in 1881 to his marriage and return to Tokyo. In this article, we will focus on the period from his unsuccessful attempt to publish a journal in Tokyo in 1907 up to the Xinhai Revolution (1911–1912), devoting a large section to the revolution itself.

1907, Tokyo

The failure to publish the journal did not deter Zhou Shuren from his studies. He continued to write essays for journals such as The Zhejiang Tide, focusing on scientific works he encountered. Among these were History of Mankind (December 1907), On Cultural Extremism (June 1908), and Treatises on the History of Science (August 1908)—pieces that encouraged readers to embrace scientific thought.

At that time, Sun Yat-sen (孙中山, right, in a 1911 photograph) was also in Japan. By the late 1890s, Sun had played a key role in organizing anti-Qing movements and had been declared a traitor by the Manchu regime. Although he traveled to the United States, Canada, several European countries, and Southeast Asia, most of his organizing efforts were carried out from Japan. The foundations of the National Democratic Revolution—the first step in China’s revolution—were laid through the tireless struggles of Sun Yat-sen and many other Chinese intellectuals. The first objective was to overthrow the monarchy.

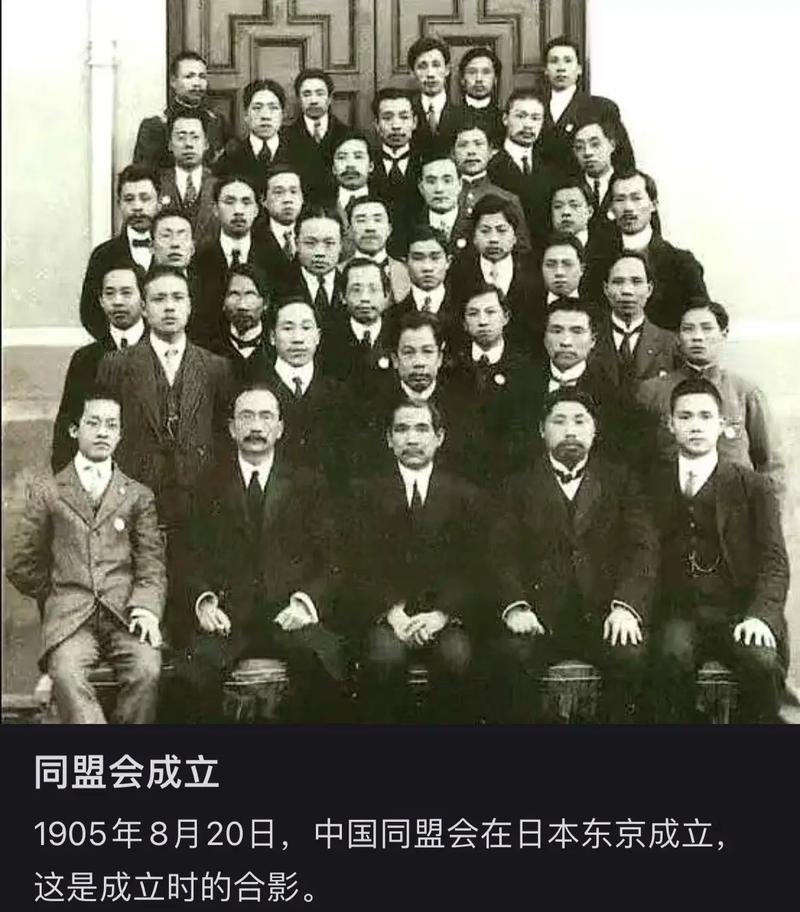

In Japan, Sun established contacts with Japanese Pan-Asianists such as Miyazaki Toten and Chinese students. On 20 August 1905, he met with figures like Huang Xing and Song Jiaoren, formally announcing the founding of the Chinese United League (Tongmenghui). This organization is regarded as the first revolutionary party in modern Chinese history. Its aim was to overthrow the monarchy and establish a republican China. (Below: Announcement of the League’s founding, 20 August 1905)

The ideological framework of the Tongmenghui was defined by Sun Yat-sen’s Three Principles of the People (三民主义): Nationalism (民族主义), Democracy (民权主义), and People’s Livelihood (民生主义). Sun elaborated on these principles in essays published between 1905 and 1907 in the journal People’s Newspaper (民报).

Alongside the theoretical struggle, Sun Yat-sen and Chinese patriots of the time organized uprisings in various parts of China. Initially, the Japanese government supported these anti-dynastic movements for opportunistic reasons, but as their anti-imperialist character became more apparent, it began to take precautions against them. Meanwhile, the Qing government, having accommodated Japanese demands to some extent, saw its relations with Japan improve. Toward the end of 1905, however, pro-revolution Chinese students in Japan began holding anti-occupation protests, with hundreds returning to China in protest.

In 1907, under pressure from the Qing envoy Yang Shu, Sun Yat-sen was expelled from Japan. With the help of his supporters, he continued his activities for a time from Vietnam, and later from other Southeast Asian countries. One of Sun Yat-sen’s most important qualities was his ability to form relationships and cooperate with influential figures of many different nationalities.

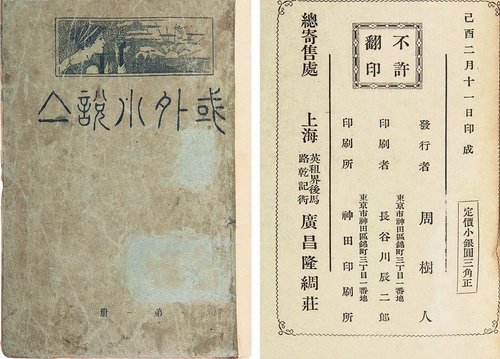

Meanwhile, Zhou Shuren spent much of his time translating foreign works from Japanese into Chinese. In 1909, in Tokyo, he and his brother Zhou Zuoren published Tales from Abroad (域外小说集, right)—a collection of stories from Russian, Northern European, and Eastern European literature. This work became one of the most important early examples of modern short story translations in China. However, of the two-volume, 1,500-copy print run, only 40–50 copies were sold. The work was “born ahead of its time,” bringing the brothers significant financial loss.

“I have no exact figures for sales in Shanghai, but I heard that about 20 copies were sold, after which there were no more buyers… At that time, short stories were rare; readers were used to traditional novels of 100–200 chapters, so short stories meant almost nothing to them.”

(Lu Xun, 1920; Preface to the new edition of Tales from Abroad*)*

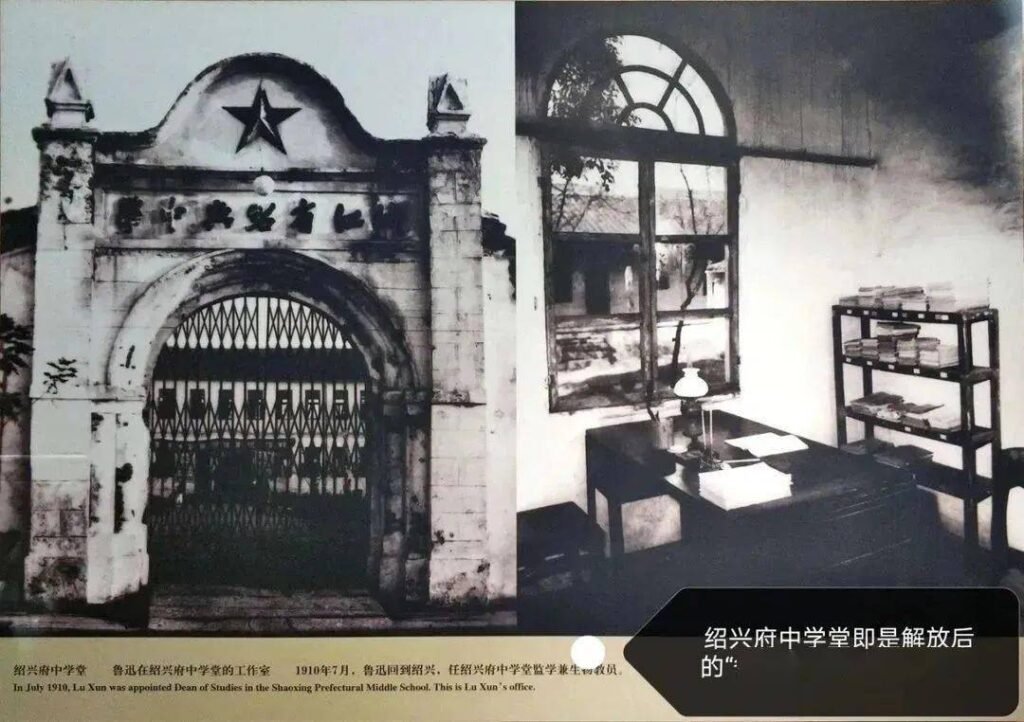

In August 1909, due to financial difficulties, Zhou Shuren decided to return to China. The prestige of having studied abroad, along with a reference from his friend Xu Shoushang, enabled him to start teaching chemistry and physiology at the Zhejiang Normal School in Hangzhou. A year later, in 1910, he returned to his hometown Shaoxing, where he continued teaching physiology at Shaoxing Middle School (绍兴府中学, below, with Lu Xun’s office).

At the time, physiology was a new field in China, and Zhou Shuren could be considered one of its pioneers. In addition to translating Japanese teaching materials, he took students outside to collect plant and animal specimens and based his lessons on these.

Toward the Xinhai Revolution

Between 1906 and 1911, the Tongmenghui organized more than ten failed uprisings. One of these, the Huanghuagang Uprising (27 April 1911), failed but became a symbol of revolutionary spirit. Eighty-six revolutionaries lost their lives; only seventy-two bodies were found. These seventy-two were buried together later that year in Huanghuagang, northeast of Guangzhou. Today, the Huanghuagang Seventy-Two Martyrs’ Tomb (黄花岗七十二烈士墓) is on the list of “Nationally Protected Cultural Relics” and is open to visitors (below).

Another decisive moment was the Sichuan Railway Protection Movement (保路运动). In September 1911, the people of Sichuan rose up against the Qing government’s decision to transfer to foreign banks the concession rights for a railway built with provincial resources. The harsh suppression of the protests intensified anti-Qing sentiment not only in Sichuan but across the country.

In this tense climate, the Wuchang Uprising (武昌起义) broke out on the night of 10 October 1911 (left, symbolic image; the flag used in the uprising later served as the flag of the Chinese Republican Army from 1913–1928). Originally planned for a later date, the uprising was moved forward after revolutionary cells were exposed. The rebels captured military installations and government buildings in Wuchang. The success in Wuchang led to a collapse of morale within the Qing army and sparked a chain of uprisings across the country.

In the weeks that followed, provinces such as Hunan, Shaanxi, Jiangxi, Shanxi, Yunnan, Guizhou, Zhejiang, and Fujian declared independence from Qing rule. By early November, the strategically important city of Nanjing was also in revolutionary hands. For this reason, the Wuchang Uprising is regarded as the actual starting point of the Xinhai Revolution. The name “Xinhai” (辛亥) comes from the traditional Chinese cyclical calendar designation for that year.

At the time, Yuan Shikai (袁世凯, right, in a 1912 photograph) controlled the Beiyang Army and its modernization process. As internal unrest escaped central control entirely, Yuan was appointed Minister of the Interior and Acting Prime Minister (内阁总理大臣) by the imperial court in November 1911. Following the Wuchang Uprising and the wave of provincial independence declarations, Yuan entered negotiations with both the revolutionaries and the Qing court. He played a double game, maneuvering strategically to consolidate his own power. The regular army was under his control, while the revolutionaries lacked it; the republicans needed Yuan’s monopoly on arms to fully seize power.

Sun Yat-sen, though abroad during these events, returned to China in December 1911. On 29 December, the provisional senate meeting in Nanjing elected him Provisional President. On 1 January 1912, the establishment of the Republic of China (中华民国) was proclaimed (below, symbolic image). The dynasty had not yet fallen, and a dual power situation existed in terms of political authority.

On 20 January 1912, Sun Yat-sen wrote to Yuan Shikai, offering to relinquish the presidency to him in exchange for the overthrow of the Qing dynasty and recognition of the republic. Sun’s condition was that the republican system be maintained. Yuan accepted the offer after a calculated delay.

By 1909, Yuan had become an influential figure at court. Emperor Puyi was only six years old in 1912, and most political decisions were made by court officials and figures such as Empress Dowager Longyu. Yuan convinced the court that the war could not be won, but that they could continue living in the Forbidden City if they abdicated. Faced with the success of the internal rebellion, the semi-colonial state of the country, and economic collapse, the court accepted this proposal without much delay. In February 1912, with the signing of the “Abdication Edict” (退位詔書) by Empress Dowager Longyu, Puyi stepped down and the Qing dynasty officially came to an end.

Although from the outside the Xinhai Revolution appeared to bring a radical change of regime, to Zhou Shuren it fell far short of a true transformation. The overthrow of the monarchy did not bring about the expected change in mindset or social rebirth; revolutionary enthusiasm gave way to power struggles and factionalism.

“Then the Wuchang Uprising broke out, and afterwards Shaoxing was liberated. The next day, Fan Aineng came to town, wearing a peasant’s hat and smiling in a way I had never seen before.

‘Lao Xun*, we’re not drinking today. I want to see the liberated Shaoxing. Let’s go.’

We walked around the streets, which were filled with white flags. But in essence, nothing had changed, because the administration was still a military government formed by a few old local aristocrats. This government did not last long either. The former imperial examination graduates found a new method and decided to hold some kind of assembly. The actors in this assembly were, as always, the local gentry…”

(Lu Xun, “Fanainong,” 1926)

After the “liberation” of Shaoxing, Zhou Shuren was temporarily appointed Principal of Shaoxing Middle School, where he had been teaching. This appointment aimed to align the local education administration with the revolutionary government. During this period, Shuren both oversaw the school’s administrative affairs and sought to instill a modern educational philosophy in his students. He worked to update the school curriculum and eliminate remnants of the Qing-era education system. He particularly encouraged the addition of new courses in science and literature. However, these reforms were limited by resistance from conservative circles and financial constraints.

Lu Xun later reworked this experience into fictional form in his 1921 novella The True Story of Ah Q. Comprising nine chapters, the work depicts rural China before and after the Xinhai Revolution. Through the story of Ah Q—a wandering laborer in Weizhuang village who is hardworking yet possesses nothing, and whose very name is forgotten—Lu Xun explores social flaws such as conservatism, fatalism, and arrogance shaped by feudal culture, while exposing the revolution’s failure to truly transform society.

“The people of Weizhuang village gradually calmed down. According to reports, although the revolutionaries had entered the city, there was no major change. The old magistrate was still in office, only his title had changed; moreover, the former imperial examination graduates had been appointed to new positions.”

(The True Story of Ah Q, Chapter 7, 1921)

To be continued in the next article…

(*) Lao (老) is a familiar, friendly, and somewhat respectful form of address, used as Lao + Surname. Although Zhou Shuren first used his pen name “Lu Xun” in his 1918 work A Madman’s Diary, he used over 180 pseudonyms in his lifetime. “Lu Xun” comes from his mother Lu Rui’s surname and his childhood nickname Xunxing (讯行). The choice of surname has been interpreted as a stance against China’s traditional patriarchal surname system.

Previous article: Who is Lu Xun?

https://sinoturkishstudies.com/dunya/cin/lu-xun-%E9%B2%81%E8%BF%85-kimdir/